As I dig deeper into my family history I find myself becoming more and more interested in Jewish history throughout its existence. My ancestors came to England from Poland, Lithuania and Belarus, whilst my husband’s parents arrived here more recently from Hungary (as Holocaust survivors) and Russian Georgia. My attachment to my antecedents, both familial and Jewish people in general, urges me to visit synagogues in other countries whenever I get the chance. Not so much from a religious curiosity, but from a desire to learn about the Jews who lived in these places, and to mourn the passing of those who perished for their religious faith.

On a recent Adriatic cruise I had multiple opportunities to find out a little more about various Jewish communities, including those in Corfu, Split and Dubrovnik, finishing with the city which gave the world the word ‘Ghetto’ – Venice.

Romaniotes were the first Jewish inhabitants of Greece and her islands and their presence dates back 2000 years, although they differ from the Sephardi Jews who arrived from Spain and Portugal after 1492. These immigrants from the Iberian Peninsula were later joined by Italian Jews from Apulia on Italy’s Adriatic coast.

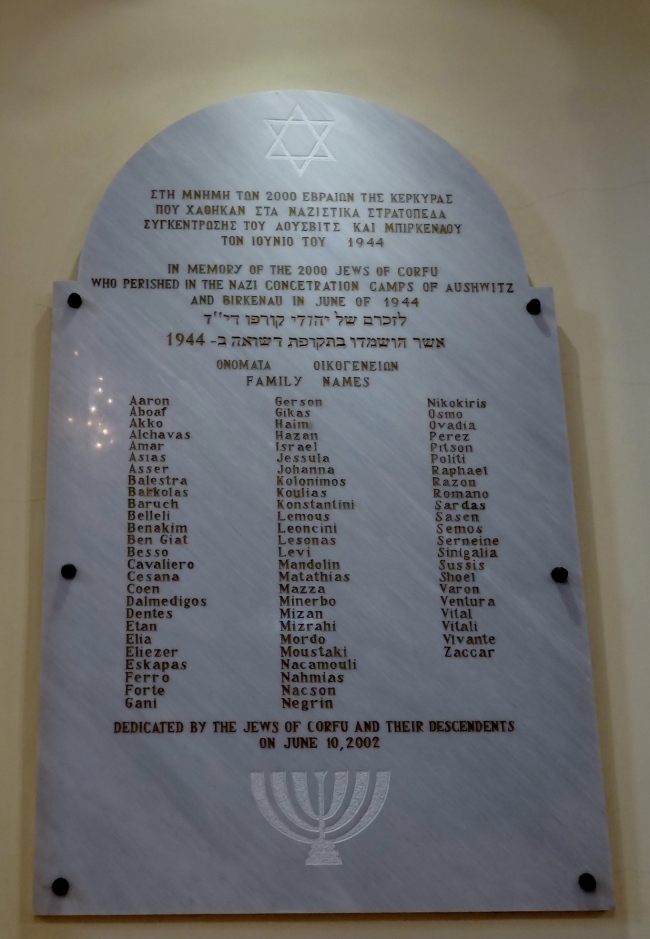

In 1622 Corfu’s Venetian rulers decreed that the Jews relocate to an area sandwiched between Porta Reale and Porta di Spilia, subsequently known as ‘Evraiki’, the name by which it is still known. Of the three synagogues in this area, two were destroyed by bombing in 1944, leaving the nineteenth-century building on Velissariou Street. The same year the Gestapo rounded up the Jewish population of 1900 (200 of whom escaped and were sheltered by fellow Greeks) and sent them to Auschwitz-Birkenau to be gassed. They are commemorated on a plaque in the building.

The current Jewish population of Corfu now numbers approximately 65 people. The Corfu synagogue was attacked by arsonists three years ago, but no evidence of this vandalism remains today.

I was particularly impressed by the unusual stained glass windows.

Split (in Croatia) has been home to a Jewish presence since the third century when Jews settled in Salona, just outside of the modern city. Four hundred years later when the city was conquered by the Avars they moved to Split where they sought refuge in Diocletian’s palace, attaching a synagogue to its western wall in the sixteenth century. A Jewish ghetto was later created on the other side of the city where a new synagogue was built in Zidovski Prolaz (the Jewish Passage). The pre-Sephardim were also joined by Sephardi Jews fleeing from the Spanish Inquisition towards the end of the fifteenth century.

From 1941 Croatia was ruled by Italian Fascists, who were supplanted in 1943 by until the arrival of the Nazis and the Croatian Ustashe. The latter transported Jews to their own concentration camps, where approximately seventy-five percent of Croatian Jews perished. The synagogue also has its own memorial to those who never returned after WW2.

Along the Dalmatian coast and within the old walled city of Dubrovnik, the synagogue boasts of being the oldest Sephardic synagogue in use and the second oldest synagogue in Europe – its older relation can be found in Prague.

The prayer house is situated on the upper floor of a medieval house at Zudioska 5 and sits above a small museum, itself a poignant reminder of the fate of Dubrovnik’s Jewish community, and of the yellow stars they were forced to wear that identified them and their religion.

On 29 March 1516 the Venetian Republic created the first Ghetto in Europe. Jews were confined between sunset and sunrise until Napoleon unlocked the gates permanently in 1797. Twenty-first century visitors to la Serenessima can now visit the Jewish Museum (opened in 1955) throughout the day at Campo del Ghetto Nuovo 2902b . The museum is the starting point of the ghetto tour and will take you to four synagogues in the area.

The Schola Levantina was the first to be built in 1538; the Schola Canton and the Schola Tedesca are both housed in the same building as the museum; the Schola Italiana (built in 1575) can also be found on Ghetto Square and the remaining synagogue, the Schola Spagnola is the largest of the five, built in the sixteenth century. Unfortunately photography is prohibited, but you will be able to find images online. For this reason I can’t quite remember which building was which, but do recall that they have all been refurbished, generally in the eighteenth century in baroque style. Of the two synagogues in general use one is used in the summer as it is cooler, and the other is used in the winter, for the opposite reason. Again I forget which is which, but this is a view of the outside of the Schola Spagnola – the Spanish Synagogue.

Further information can be found on the Ghetto Ebraico di Venezia website: http://www.ghetto.it/ghetto/en/contenuti.asp?padre=1&figlio=2. A strange fact of the Cannaregio (the ghetto area) is that the old ghetto (Ghetto Vecchio) is newer than the new ghetto (Ghetto Novo). I forgot to ask why. This is the bridge separating the two districts. I apologise for the ubiquitous tourist who always manages to get in the way.

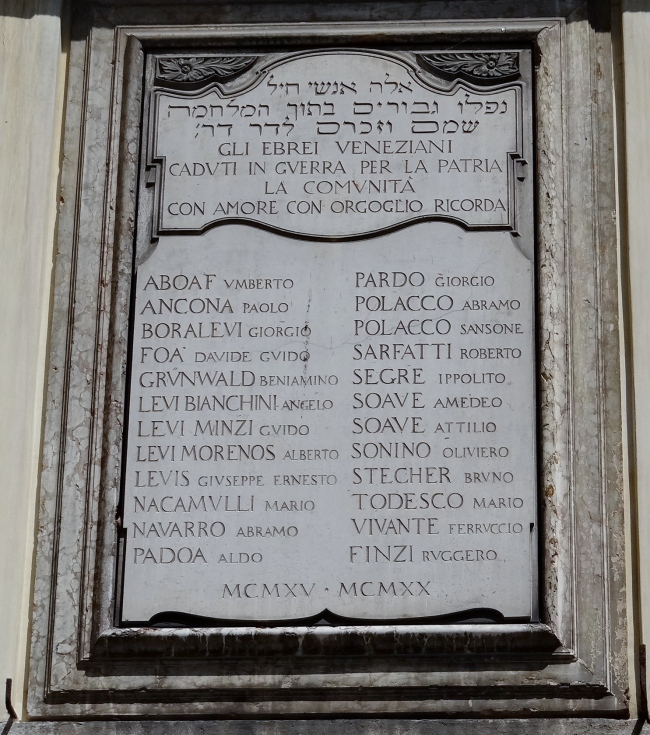

The city commemorates both those Venetians who lost their lives fighting for Italy

as well as the 6 million victims of the Holocaust.

If you are a religious Jew and find yourself in Venice on Shabbat or during a religious festival, the area is surrounded by an Eruv for carrying items and pushing wheelchairs and pushchairs, and if you are strictly observant you will also be able to find kosher food, but obviously not on Saturdays and festivals.

I would be happy to hear from others who have visited these places of Jewish history and interest and learn of their thoughts. Please excuse any shortcomings in the above. It is all written from memory from a little over a month ago and no notes were taken.